Guest Post

For decades, the medical community viewed the opioid crisis primarily through a lens of physical dependence. The narrative was straightforward: a patient takes a pill for back pain or post-surgical recovery, the body becomes habituated, and the patient requires the drug to function physically. However, a groundbreaking investigation carried out by scientists at the Ibogaine Clinic in Cancun, Mexico, is challenging this singular view, offering fresh perspectives on the profound influence opiates have on the human psyche.

The study illuminates a complex biological reality: opiates do not merely manage physical discomfort. They fundamentally alter the architecture of the brain, creating a deep, physiological bridge between physical pain and emotional distress.

This new data suggests that the mechanism of addiction is far more intricate than previously understood, involving the rapid development of new receptor sites that bind our emotional well-being to the presence of the drug.

The Receptor Explosion: Supply and Demand in the Brain

To understand the findings of the Cancun study, we must first look at the basic mechanics of the brain. The human brain naturally produces endogenous opioids—chemicals like endorphins that manage pain and regulate mood. We have specific “parking spots” or receptors for these chemicals.

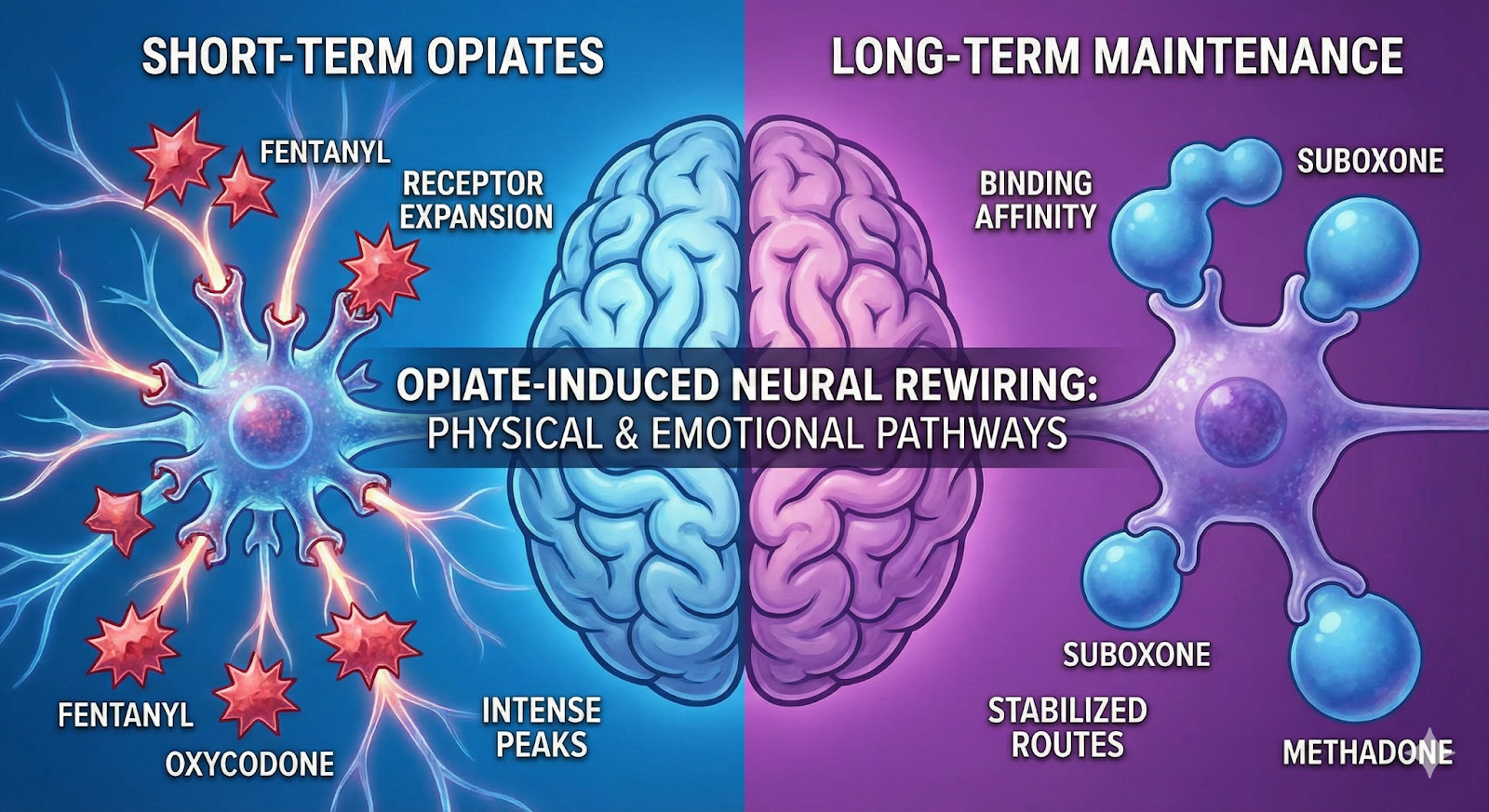

The investigation indicates that when a person introduces powerful exogenous opiates—such as fentanyl, oxycodone, or hydrocodone—the brain is overwhelmed. The study posits that these short-term opiates don’t just fill existing receptors; they trigger a biological demand for more.

The brain, in an attempt to maintain homeostasis amidst this flood of dopamine and pain relief, actually boosts the development of opiate receptors. It builds more “parking spots” to accommodate the influx of chemicals.

This is the biological basis of tolerance. As the number of receptors expands, the user needs more of the drug to fill them and achieve the same effect. But the study highlights a darker consequence of this proliferation: the creation of interlinked routes.

The Intersection of Physical and Emotional Pain

Perhaps the most profound insight from the Ibogaine Clinic’s research is the confirmation that these new receptor pathways do not distinguish between a broken bone and a broken heart.

The study indicates that opiates facilitate the formation of interlinked routes that control both physical and emotional pain. In the brain’s newly rewired circuitry, emotional distress and physical agony travel the same highway.

This explains why long-term opiate users often report a “numbing” of their emotional landscape. The drugs are effectively hijacking the emotional processing centers. However, this creates a devastating debt. When the individual discontinues the drug, those millions of newly grown receptors are suddenly left empty.

The study describes this as a process where the additional receptors “start to diminish” or starve. Because the routes are interlinked, the withdrawal is not just a physical flu-like experience; it is a profound emotional crash. The patient experiences physical torture alongside raw, unfiltered emotional suffering—anxiety, grief, and despair—because the machinery built to regulate these emotions is suddenly offline.

The Tale of Two Opiates: Short-Term vs. Long-Term Maintenance

The scientists at the Ibogaine Clinic drew important distinctions between the types of opiates and how they manipulate this receptor network.

1. Short-Term Opiates (Fentanyl, Oxycodone, Hydrocodone)

These drugs are characterized by their intensity and short half-lives. The investigation links these substances specifically to the expansion of opiate receptors. Because the drug enters and leaves the system quickly, it creates a volatile cycle of flooding and starvation, prompting the brain to aggressively build more receptors to capture every molecule. This rapid expansion is what accelerates the severity of addiction.

2. Long-Term Maintenance Opiates (Suboxone, Methadone)

The study offers a critical perspective on “maintenance” medications often used to treat addiction. While drugs like Suboxone (buprenorphine) and methadone are vital for harm reduction, the research illuminates why they are so difficult to quit.

These drugs work by establishing a powerful binding affinity to the receptors. They are “sticky.” They park in the receptor spots and stay there for a long time, blocking other opiates from entering and keeping the receptor satisfied to prevent withdrawal.

However, the study notes that these medications still maintain the “interlinked routes.” They do not necessarily reduce the number of receptors (down-regulation) to pre-addiction levels; rather, they address the addiction by keeping the expanded receptor count occupied. They continue to control the interlinked emotional and physical discomfort pathways.

This creates a “golden handcuffs” scenario for many patients. While they are stable and no longer seeking illicit drugs, their brain architecture remains altered. They remain tethered to a chemical dependency to manage their emotional and physical equilibrium.

The “Diminishing” Phase: The Agony of Cessation

The investigation paints a stark picture of what happens when these drugs are removed. Whether a patient is coming off fentanyl or Suboxone, the mechanism of suffering is rooted in the biology of the receptors.

As the study states, “when an individual discontinues the drug, these additional receptors start to diminish.”

This “diminishing” is a chaotic biological event. The brain is shouting for a chemical that isn’t there. Because of the interlinked routes discovered by the researchers, the lack of binding causes a dual-system failure. The body screams in pain (restless legs, nausea, muscle aches), and the mind screams in panic (depression, insomnia, terror).

This validates what many in the addiction field have long suspected: relapse is rarely a failure of willpower. It is a physiological reaction to the agony caused by empty, starving receptors that control the core of human feeling.

Implications for the Future of Treatment

Why does this investigation matter?

If we understand that addiction is physically structural (the growth of extra receptors) and emotionally interlinked, we can better understand why talk therapy alone often fails for acute opioid addiction, and why “cold turkey” methods have such low success rates.

The research coming out of Cancun suggests that true healing requires more than just detoxing the drug from the blood. It requires a strategy to address the receptors themselves.

This perspective aligns with the growing interest in treatments that can accelerate the “down-regulation” of these receptors—effectively pruning the overgrown tree back to its healthy state—rather than just keeping the branches occupied with maintenance drugs.

For those grappling with opioid addiction, this research offers validation. The intensity of the struggle is not “all in your head”—or rather, it is in your head, but it is rooted in tangible, biological structures that have been built by the drugs.

By acknowledging the interlinked nature of physical and emotional pain, we can move toward more compassionate, scientifically grounded treatments that address the whole person—not just the symptoms of withdrawal, but the rewired architecture of the mind.